The Herald

January, 1984

Personality Interview

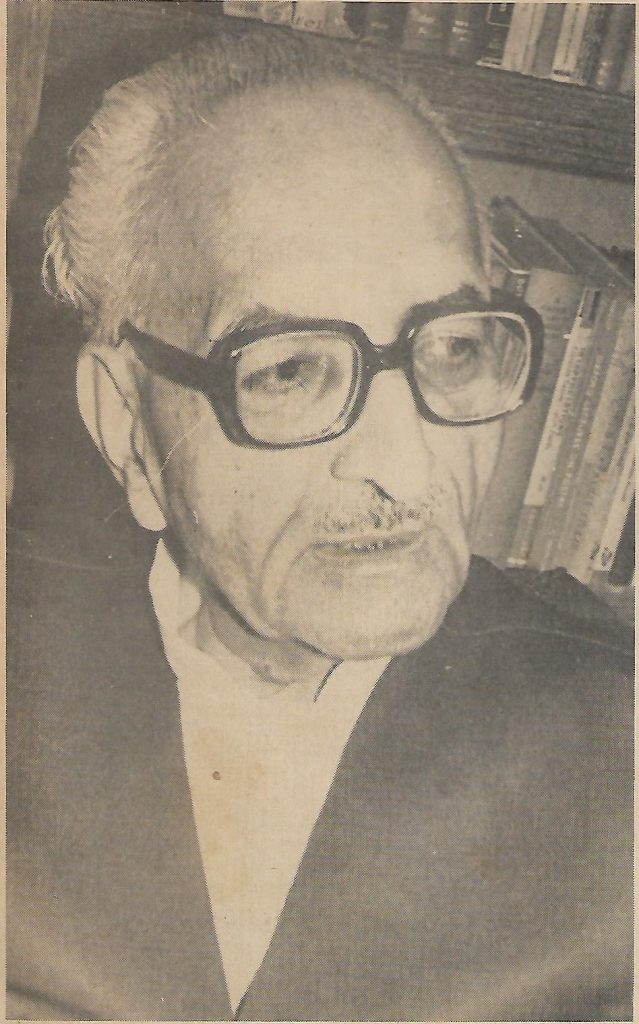

Mian Mumtaz Mohammad Khan Daultana

By Sadiq Jafri

Mian Mumtaz Mohammad Khan Daultana, 66, is one of Pakistan’s most controversial politicians. He belongs to one of the biggest landowning families of Punjab (second among the top fourteen of the province). His father, Khan Ahmad Yar Khan, was awarded the title “Khan Bahadur” in recognition of the family’s services to the Empire.

In the crucial period between the Quaid’s death and Ayub Khan’s Martial Law, when overnight changes in the central and provincial governments became routine, and ultimately led to the death of democracy and the beginning of martial law, Mian Daultana was one of the most important and influential feudal bureaucrat politicians.

As Chief Minister of Punjab before the 1958 Martial Law, Mian Daultana is generally held responsible for funning the first ever anti-Qadiani riots, which were aimed primarily at dislocating Khwaja Nazimuddin’s government. While officially Mian Saheb was issuing appeals for peace, he is accused of having secretly created and financed certain organizations which were instrumental in provoking anti-Qadiani sentiment. Mian Daultana was questioned by the Munir Enquiry Commission about his alleged involvement in the Qadiani incident and his statement was included in the Commission’s report. However, like other such reports, this too was never made public.

Today, Mian Saheb lives a retired life in his spacious bungalow set amidst acres of land in Garhi Shahu, the busy city area of Lahore. But retirement has not dulled his interest in politics. Physically trim and mentally alert, Mian Saheb answered questions on the country’s current political situation without mincing his words.

Mian Saheb’s face lights up when he recalls the ‘good’ old days, the first eleven years of Pakistan. With remarkable confidence, he praises and defends the politicians’ role before the 1958 Martial Law and nearly three decades later, is still confident that given a chance, the politicians can do better. Below follows an interview with Mian Saheb.

Q. In 1971 Punjab was accused of committing excesses against the Bengalis which compelled the latter to break away from the federation and create a new homeland. The same charge is being levelled against the Punjab, particularly against the central government, by the other three provinces today. Are the Punjabis really opposed to giving a fair share to others?

A. When Punjab is mentioned in this reference, it doesn’t include the common people of Punjab. A very few people were responsible for this state of affairs.

Actually, there is no such thing as a united Punjabi entity. Ethnically and historically, the people living in this province don’t have as much in common as those living in Sind have. We speak Punjabi but feel ashamed of it. There is, in fact, no individual personality trait of a Punjabi like there is of a Sindhi.

All these problems are part of the frustration which emerges out of lack of participation. This would not have happened in a democratic government. In that system, everyone gets his share. Ministries can’t be made without compromises, which indirectly encourages unity.

What happened in 1958 was that power was usurped by autocrats. Punjab had always had an overwhelming majority in the army, even before the inception of Pakistan. Still, Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan were not Punjabis. Ziaul Haq is the first Punjabi. However, it’s true that Punjab has always ruled through the army and so the sense of isolation and deprivation among the people of other provinces has grown, because the dictatorship has had the face of Punjab. There was no collective conspiracy of Punjabis. This would have been possible only if the Punjabis ganged up in a democratic set-up and tried to exploit smaller provinces.

Today, the Punjabis are more aware about conditions than they were about Bengal in the past, and want to dispel the impression of being unjust to others. But we can only do that if someone is ready to listen. There are no parties, so how can the smaller provinces be assured that they will get a fair share? Democracy is the only way. Theoretically one can oppose it, but practically there is no other way. Rights cannot be given through words alone.

Q. Why hasn’t the Punjab produced any leadership worth the name? What are your views on the present lot of politicians from the Punjab?

A. The first part of your question is correct, and has been the case since 1900. We tried our best during the Pakistan Movement but the province failed to produce a leadership to match the standards set by other provinces.

There are several reasons for this. One is that Punjabis gained political consciousness very late, in fact too late. Till as late as 1946, for example, Punjab was not even supporting the Muslim League or the Quaid-e-Azam. Punjab was far more backward than the other provinces, particularly Sind, in the freedom struggle. Fazle Hussain and Sir Sikandar Hayat are prime examples but they are not relevant here.

Secondly, when we talk about Punjab, we take it as a united entity, while actually there is no such thing. The geographical boundaries were set by the British and it was bifurcated during Partition. But ethnically and historically, the people living in this province don’t have as much in common as those living in Sind have. We speak Punjabi but feel ashamed of it. There is no individual personality trait of a Punjabi like there is of a Sindhi.

Thirdly, Punjab is well off economically, educationally and in regard to services. So, there is none of the tension and bitterness which throws up good leadership. Still, the Punjab, being the most important province, could have become a link for uniting other provinces. But it failed in this duty, mostly because democracy has been non-existent for the past 25 years.

Bhutto was a Sindhi, but the complexion of his government was Punjabi. What’s happening in Sind has been building up since 1958. It was not halted even during Bhutto’s rule, in the sense that no basic changes took place in that period … But I’m afraid that if feelings of deprivation in Sindhis are brushed aside and crushed forcefully, there’s every likelihood of it taking a similar turn to that of 1971. And then it will not be a mere separation. It will be the end of the whole thing.

About Punjab’s present leadership, I can’t give any opinion because there is no way to judge any politician. There is no politics.

Q. What about the lower middle and lower class of Punjabis? What are their hopes and fears?

A. Over 70 percent of the people living in Punjab are facing the same problems as people in other provinces. The poor of Punjab are as deprived and desperate as the poor living in other areas. The lack of social and economic justice affects everybody equally.

Feudals have never opposed the government of the day in the whole history of the subcontinent. Our landlords are not big or powerful enough to rule over their lands without the patronage of the regime. In Punjab, feudal landlords have never gone against the regime and I’m not ready to accept that the feudal landlord of Sind has overnight become a revolutionary.

Q. Do you think Punjab is responsible for the Sindhis current sense of isolation since it has not actively participated in the recent movement?

A. All the provinces have participated equally in the movement. But, of course, it had a catalytic effect on Sind because, there, the sense of deprivation was stronger and clearer. Naturally, Sindhis will get angry if Punjab does not share their problems. And, you know, Punjab will only rule if Pakistan remains. The country cannot exist without any single province. Therefore, I believe, they (the rulers) are more worried about the situation than we think. We should not miss this moment when the problem can easily be solved.

Q. Do you agree with the contention that the agitators in Sind were a handful of “miscreants” and mercenaries dancing to the tune of Sindhi feudal interests?

A. Agitators should not be called criminals. Sindhis are patriots and they have done their duty towards the country, more than we have. Yet their sense of deprivation is increasing day by day. It is not the number of agitators which is important. Even if there are only a few, it still means that something is wrong. A cure is necessary and the reasons for such an event must be probed to find out what compelled the common people of Sindh to approve of such activities.

About feudal, I don’t believe they have ever opposed the government of the day in the whole history of the subcontinent. Our landlords are not big or powerful enough to rule over their lands without the patronage of the regime. In Punjab, feudal landlords have never gone against the regime and I’m not ready to accept that the feudal landlord of Sind has become a revolutionary overnight. The real reason is that these feudal have sacrificed their immediate interests only to win over people’s sympathies.

Q. On the subject of Sind, do you think the bureaucracy has been trying to do away with Sind as a separate entity in the federation, and that the past six years have aggravated the sense of deprivation in Sindhis?

A. I’ll tell you something. Bhutto had won majority seats in Punjab, and not in Sind. He was a Sindhi but the complexion of his government was Punjabi. I think what’s happening in Sindh has been building up since 1958. It was not halted even during Bhutto’s rule, in the sense that no basic changes took place in that period also. True, had the 1973 Constitution been in force and elections held regularly, there could have been some changes. But it’s wrong to say that the present regime has something special against Sindhis.

Punjab has always ruled through the army, and therefore, the sense of isolation and deprivation has grown among the people of the other provinces because the dictatorship has always had the face of Punjab. Today, the Punjabis are more aware about past mistakes and want to dispel the impression of being unjust to others.

Q. Do you see any similarity in the conditions prevailing in 1971 in East Pakistan to those in Sind today? Or is it just a general campaign against the status quo, as in 1977?

A. I hope there’s no similarity to either. One should always be an optimist but I’m afraid that if feelings of deprivation in Sindhis are brushed aside and crushed forcefully there’s every likelihood of it taking a similar turn to 1971. In that event, it won’t be a mere separation. It will be the end of the whole thing.

Q. Do you think the mistakes of 1971 will be repeated? How optimistic are you about the future?

A. I wish there was democracy in Pakistan. Other solutions barring democracy, would have been possible only if there had been equal representatives from every province in the army and the establishment. I feel very confused. We need brisk decisions as we really don’t have much time left. I pray the rulers understand what has in fact gone wrong. I’m sure they’re well aware of the problems and will deal with the situation like true statesmen.