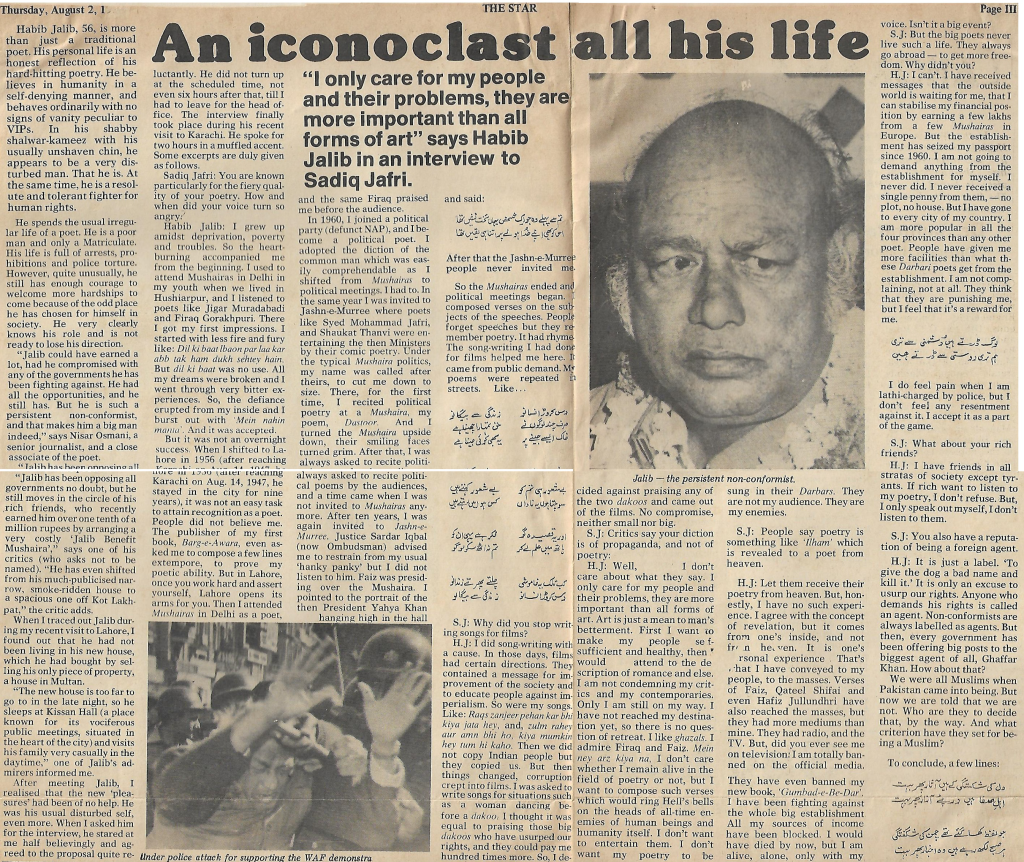

The Star

August 2, 1984

Habib Jalib

“I only care for my people and their problems, they are more important than all forms of art” says Habib Jalib in an interview to Sadiq Jafri.

Habib Jalib, 56, is more than just a traditional poet. His personal life is an honest reflection of his hard-hitting poetry. He believes in humanity in a self-denying manner, and behaves ordinarily with no signs of vanity peculiar to VIPs. In his shabby shalwar kameez with his usually unshaven chin, he appears to be a very disturbed man. That he is. At the same time, he is a resolute and tolerant fighter for human rights.

He spends the usual irregular life of a poet. He is a poor man and only a Matriculate. His life is full of arrests, prohibitions and police torture. However, quite unusually, he still has enough courage to welcome more hardships to come because of the odd place he has chosen for himself in society. He very clearly knows his role and is not ready to lose his direction.

“Jalib could have earned a lot, had he compromised with any of the governments he has been fighting against. He had all the opportunities, and he still has. But he is such a persistent non-conformist, and that makes him a big man Indeed,” says Nisar Osmani, a Senior journalist, and a close associate of the poet.

“Jalib has been opposing all governments no doubt, but he still moves in the circle of his rich friends, who recently earned him over one-tenth of a million rupees by arranging a very costly Jalib Benefit Mushaira’,” says one of his critics (who asks not to be named). “He has even shifted from his much-publicized narrow, smoke-ridden house to a spacious one-off Kot Lakh pat,” the critic adds.

When I traced out Jalib during my recent visit to Lahore, found out that he had not been living in his new house, which he had bought by selling his only piece of property, a house in Multan.

“The new house is too far to go to in the late night, so he sleeps at Kissan Hall (a place known for its vociferous public meetings, situated in the heart of the city) and visits his family very casually in the daytime,” one of Jalib’s admirer informed me.

After meeting Jalib, realized that the new pleasures had been of no help. He was his usual disturbed self, even more. When I asked him for the interview, he stared at me half-believingly and agreed to the proposal quite reluctantly. He did not turn up at the scheduled time not even six hours after that, till had to leave for the head office. The interview finally took place during his recent Visit to Karachi. He spoke for two hours in a muffled accent. Some excerpts are duly given as follows.

Sadiq Jafri: You are known particularly for the fiery quality of your poetry. How and when did your voice turn so angry:

Habib Jalib: I grew up amidst deprivation, poverty and troubles. So, the heart burning accompanied me from the beginning I used to attend Mushairas in Delhi in my youth when we lived in Hushiarpur, and I listened to poets like Jigar Muradabadi and Firaq Gorakhpuri. There I got my first impressions. I started with less fire and fury like: Dil ki baat lbaon pur lakar abb tak ham dukh sehtey hain. But dil ki baat was no use. All my dreams were broken and I went through very bitter experiences. So, the defiance erupted from my inside and I burst out with “Mein nahin manta.” And it was accepted.

But it was not an overnight success. When I shifted to Lahore in 1956 after reaching Karachi on Aug. 14, 1947, he stayed in the city for nine years), it was not an easy task to attain recognition as a poet. People did not believe me. The publisher of my first book, Barg-e-Awara, even asked me to compose a few lines extempore, to prove my poetic ability. But in Lahore, once you work hard and assert yourself, Lahore opens its arms for you. Then I attended Mushairas in Delhi as a poet, and the same Firaq praised me before the audience.

In 1960, I joined a political party (defunct NAP), and I become a political poet. I adopted the diction of the common man which was as easily comprehend able as I shifted from Mushairas to political meetings. I had to. In the same year I was invited to Jashn-e-Murree where poets like Syed Mohammad Jafri, and Shaukat Thanvi were entertaining the then Ministers by their comic poetry. Under the typical Mushaira politics, my name was called after theirs, to cut me down to size. There, for the first time, I recited political poetry at a Mushaira, my poem, Dastoor. And I turned the Mushaira upside down, their smiling faces turned grim. After that, I was always asked to recite political poems by the audiences, and a time came when I was not invited to Mushairas anymore. After ten years, I was again invited to Jashn-e-Murree. Justice Sardar Iqbal (now Ombudsman) advised me to restrain from my usual ‘hanky panky’ but I did not listen to him. Faiz was presiding over the Mushaira. I pointed to the portrait of the then President Yahya Khan hanging high in the hall and said:

تم سے پہلے جو اک شخص یہاں تخت نشیں تھا

اس کو بھی اپنے خدا ہونے کا اتنا ہی یقیں تھا

After that the Jashn-e-Murree people never invited me.

So, the Mushairas ended and political meetings began. I composed verses on the subjects of the speeches. People forget speeches but they remember poetry. It had rhyme. The songwriting I had done for films helped me here. It came from public demand. My poems were repeated in streets. Like…

!دس کروڑ انسانو زندگی سے بیگانو

صرف چند لوگوں نے حق تمھارا چھینا ہے.

خاک ایسے جینے پر یہ بھی کوئی جینا ھے

بے شعور ہی تم کو بے شعور کہتے ہیں

سوچتا ہوں یہ ناداں کسی ہوا میں رہتے ہیں

اور یہ قصیدہ گو فکر ہے یہی ان کو

ہاتھ میں علم لے کر تم نہ اٹھ سکو لوگو

کب تلک یہ خاموشی چلتے پھرتے زندانو

دس کروڑ انسانو زندگی سے بیگانو

S.J: Why did you stop writing songs for films?

H.J: I did song-writing with a cause. In those days, films had certain directions. They contained a message for improvement of the society and to educate people against imperialism. So were my songs Like: Raqs zanjeer pehan kar bhi kiya jata hey, and, zulm rahey aur amn bhi ho, kiyu mumkin hey tum hi kaho. Then we did not copy Indian people but they copied us. But then things changed, corruption crept into films. I was asked to write songs for situations such as a woman dancing before a dakoo. I thought it was equal to praising those dakoos who have usurped our rights, and they could pay me hundred times more. So, I decided against praising any of the two dakoos and came out of the films. No compromise, neither small nor big.

S.J: Critics say your diction is of propaganda, and not of poetry:

H.J: Well, I don’t care about what they say. I only care for my people and their problems, they are more important than all forms of art. Art is just a mean to man’s betterment. First, I want to make my people self-sufficient and healthy, then I would attend to the description of romance and else.

I am not condemning my critics and my contemporaries. Only I am still on my way. I have not reached my destination yet, so there is no question of retreat. I like ghazals. I admire Firaq and Faiz. Mein ney arz kiya na. I don’t care whether I remain alive in the field of poetry or not, but I want to compose such verses which would ring Hell’s bells on the heads of all-time enemies of human beings and humanity itself. I don’t want to entertain them. I don’t want my poetry to be

want to compose such verses ne which would ring Hell’s bells on the heads of all-time the enemies of human beings and All humanity itself. I don’t want to entertain them. I don’t want my poetry to be sung in their Darbars. They are not my audience. They are my enemies.

S.J: People say poetry is something like ‘Ilham’ which is revealed to a poet from heaven.

H.J: Let them receive their poetry from heaven. But honestly, I have no such experience. I agree with the concept of revelation, but it comes from one’s inside, and not from heaven. It is one’s personal experience. That’s what I have conveyed to my people, to the masses. Verses of Faiz, Qateel Shifai and even Hafiz Jullundhri have also reached the masses, but they had more mediums than mine. They had radio, and the TV. But, did you ever see me on television. I am totally banned on the official media.

They have even banned my new book, ‘Gumbad-e-Be-Dar’. I have been fighting against the whole big establishment. All my sources of income have been blocked. I would have died by now, but I am alive, alone, only with my voice. Isn’t it a big event?

S.J. But the big poets never live such a life. They always go abroad―to get more freedom. Why didn’t you?

H.J. I can’t. I have received messages that the outside world is waiting for me, that can stabilize my financial position by earning a few lakhs from a few Mushairas in Europe. But the establishment has seized my passport since 1960. I am not going to demand anything from the establishment for myself. I never received a single penny from them, ―no plot, no house. But I have gone to every city of my country. I am more popular in all the four provinces than any other poet. People have given me more facilities than what these Darbari poets get from the establishment. I am not complaining, not at all. They think that they are punishing me, but I feel that it’s a reward for me.

لوگ ڈرتے ہیں دشمنی سے تیری

ہم تری دوستی سے ڈرتے ہیں

I do feel pain when I am lathi-charged by police, but I don’t feel any resentment against it. I accept it as a part of the game.

S.J: What about your rich friends?

H.J: I have friends in all stratas of society except tyrants. If rich want to listen to my poetry, I don’t refuse. But I only speak out myself, I don’t listen to them.

S.J: You also have a reputation of being a foreign agent.

H.J: It is just a label. ‘To give the dog a bad name and kill it.’ It is only an excuse to usurp our rights. Anyone who demands his rights is called an agent. Non-conformists are always labeled as agents. But then, every government has been offering big posts to the biggest agent of all, Ghaffar Khan. How about that?

We were all Muslims when Pakistan came into being. But now we are told that we are not. Who are they to decide that, by the way. And what criterion have they set for being a Muslim?

To conclude, a few lines:

دل کی شکستگی کے ہیں آثار پھر بہت

اہلِ صفا ہیں درپے آزاد پھر بہت

جو لفظ کھا گئےتھے چمن کی شگفتگی

ہر صبح لکھ رہے ہیں وہ اخبار پھر بہت