The Herald

October, 1986

By Sadiq Jafri and Shahid Mubashir

Sadiq Jafri in Karachi and Shahid Mubashir in Rahimyar Khan investigate the story of the export of Pakistani children to the UAE to serve as riders in the traditional camel races there. Although the earlier horror story of the boys being whipped seems to be untrue, a flourishing trade is definitely being conducted by parents eager to earn quick Petro money through their children.

On September 14, six men and seven boys, aged between three and five, were detained at Karachi airport while boarding a flight to Dubai: their papers were not in order. But immigration authorities uncovered a more startling fact when they examined their documents: the children were traveling on UAE employment visas.

It did not take much investigation to discover precisely what employment: the boys, all from villages in Rahimyar Khan district, had been hired as riders in the UAE’s traditional camel races. The FIA took the children and the six men accompanying them into custody, pending investigation of whether the children had been kidnapped or were being “exported by their parents. Next day Dawn carried a horrifying report describing what lay in store for the children: the kids were to be tied to the camels’ back and whipped so that their screams would encourage the racing camels to run faster. One child was reported to have died during a race.

The revelations aroused a storm of outrage. Subsequent investigation revealed that the earlier story about the children being tied to the camels’ tails and whipped was untrue. FIA investigations also revealed that the children had not been kidnapped: the adults accompanying them were relatives – fathers, brothers or uncles.

The disclosure confirmed a starkly poignant fact: a minor trade in the export of kids to serve as riders in camel races in the oil-rich sheikhdoms of the UAE is being conducted by families in the parched areas of southern Punjab Nearly 200 Pakistani boys, ranging in age from three to six, have so far been exported.

The boys are tied not to the camels’ tails but to their backs. No beatings are involved, but there is the ever-present danger that the rider might fall down and be trampled in the race. One child has already died in this fashion.

The concept of using children to earn an extra buck through an occupation patently fraught with danger is by any standard horrific. But to the parents involved, the camel kid trade is just another highly lucrative mode of employment. They are reluctant to accept that camel-racing is a hazardous job for young kids. But they admit that even if a small risk is involved, the – payment is large – much larger in fact, they earn what they would expect to earn in the whole of their lives.

Mohammad Yasin, one of the men detained by the FIA, was born in Faisalabad, but has married and settled in Rahimyar Khan. He was a daily wage laborer before he got this opportunity to a better life. “The pay is Rs. 5,000 a month per boy,” he said, “and an equal salary for the guardian.” Since residential accommodation and food are free, he had anticipated saving the entire sum of Rs. 10,000 a month.

Asked why children, not adults, are used as riders, he replied it was because children weigh less. Asked why the Arabs did not use their own children for the purpose, he had no answer.

His son, Shahzad, 5, seemed quite at home in the FIA office. Smiling, he came forward and whispered his name. Asked where he was going, he replied “Abu Dhabi.”

Why was he going? “To ride camels,” he replied proudly.

Did he know how to ride a camel? The boy looked puzzled, and turned to his father. Mohammad Waseem promptly replied that the child was going to be provided a year’s training before he was allowed to ride in a proper race.

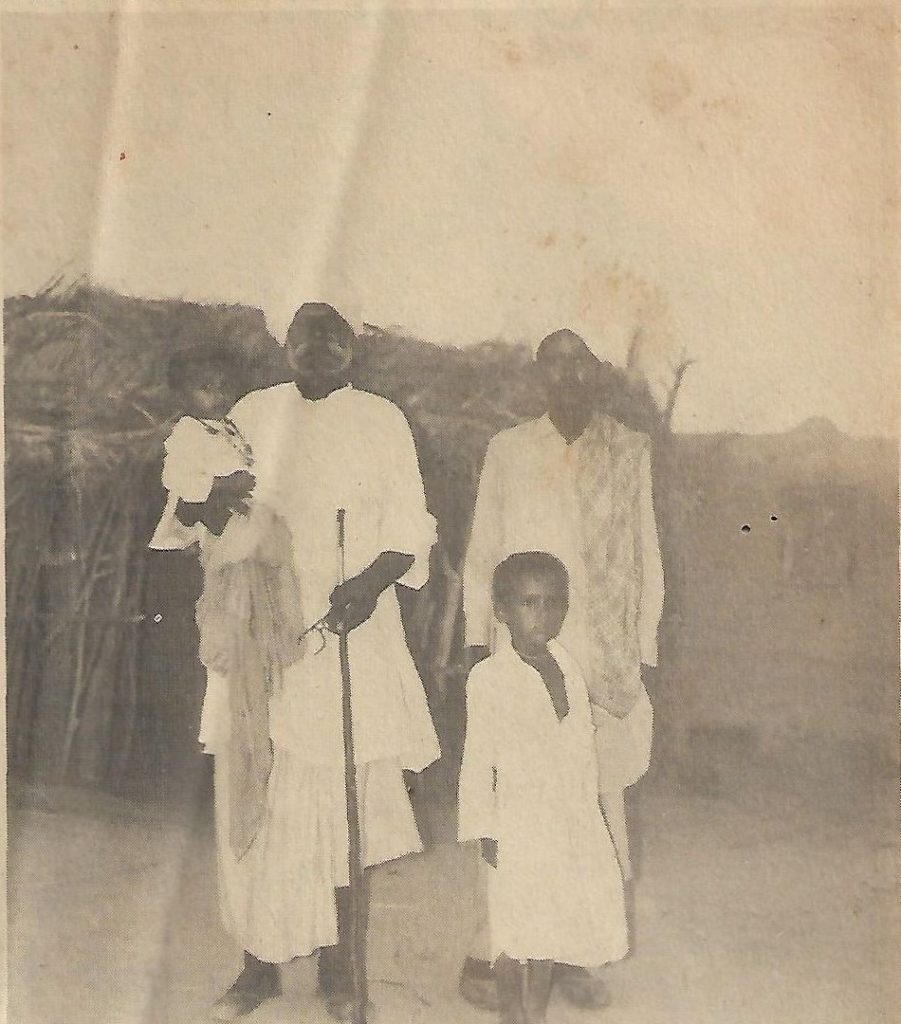

Mohammad Saleem, a young man, had two children in his charge: Mohammad Rafiq, 4, his youngest brother, and Elahi Bakhsh, 5, his who appeared to be the youngest, kept crying constantly. He seemed to be sick, but asked if the child was unwell, his father casually replied, “He’s all right, just restless.”

A vast tract of Rahimyar Khan, the southernmost district of the Punjab, is desert. Although the remaining land is fertile, agricultural production is badly affected by an acute shortage of irrigation water, and by salinity and waterlogging. Because the area is situated towards the end of the canals flowing from the north, local farmers do not usually receive much water when their turn arrives – and this happens most of the year.

A week after the camel-kid scandal broke, news of the detention in nephew. They are residents of Chak No. 110, tehsil Khanpur in Rahimyar Khan district.

“Hundreds of children have gone to Abu Dhabi from Rahimyar Khan for the same purpose,” he disclosed.

A hotel owner in Khanpur attributes the use of children in camel races to the “Arabs” obsession with speed. They buy special light- weight camels for the races, and control their diet to keep down their weight. The ideal weight for a rider is about 15 kilograms, which is why such young children are imported. Those who cross the weight limit become useless; so the age limit tends to be seven or eight.”

According to him the races are held during the winter months, mainly on Fridays. If the children and their guardians remain in the Emirates during the summer, they continue to receive their salaries and all other benefits.

Mohammad Saleem also disclosed that two of his younger brothers were already employed in Abu Dhabi as riders and had been there for the past four years. One of them had grown too old for the job, and was likely to return this year.

The eldest of the children remained silent throughout the conversation, staring out of a window. Another boy, Karachi of Rahimyar Khan’s Dubai bound group had filtered through to the area. But the local population was generally tightlipped about the affair. Most villagers are reluctant to admit that children are sent to Abu Dhabi for the purpose, particularly people in the area to which the detainees belong.

Chak No. 110, the prosaically titled village in the Khanpur tehsil of Rahimyar Khan district, is where the trail leads. This is the village Mohammad Saleem, one of the men arrested in Karachi with a younger brother aged four and a nephew of five is alleged to have come from. It is one of the several relatively recent ‘canal colonies’, villages inhabited mainly by settlers from central Punjab. The villagers claim they do not know anyone by the name of Mohammad Saleem. Yes, they have heard the news of the children’s arrest, but they do not know any of the people arrested in Karachi, nor have they ever heard of children going to Abu Dhabi as camel riders.

In Chak No. 109 nearby, however, a housewife becomes attentive when someone mentions Abu Dhabi. She reveals that three of her sons are in Abu Dhabi. The eldest has been there for a while; the youngest, aged seven, left just this year. She does not know what her children do there, and says she knows nothing about their being used in camel racing. She proudly pulls out pictures of her sons and a large photograph showing the interior of her house. A conscious effort seems to have been made to cram all the electronic equipment in the house – an air conditioner, a tape-recorder and a VCR into a single frame. Each of her three sons is paid Rs. 5,000 a month, she discloses. She also reveals that the family owns some land, but the water shortage has rendered most of it uncultivable.

A crowd gathers while this conversation is in progress. It emerges that apart from the woman’s three sons, other children from the village have also gone to Abu Dhabi. But everyone is adamant that it is not as camel riders. They maintain that the kids only milk the camels.

Surprisingly, there are no camels or cameleers in this part of the district. People are mainly small land-holders or traders or shopkeepers. There are pucca roads, a high school, a middle school, a few sub-health centers, and banks.

In Khanpur, the nearest town, people are aware that children from the outlying areas are sent to the UAE, but claim they do not know why. A local resident, approached for information, is reluctant to talk at first but is later persuaded. He knows that children are being sent to ride racing camels in the UAE – and terms it one of the blessings of the proximity of the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi, who owns a palace near Rahimyar Khan. The people of the area have benefited financially from the Sheikh’s presence in different ways. The Sheikhs have local agents in the area, and have established residential colonies for employees and other local connections.

One person who has obviously benefited from the Sheikh’s largesse, was penniless five years ago. Now he owns an air-conditioned hotel in Khanpur, frequented by the Sheikh’s considerable entourage. At the reception counter, there are several men in flowing white Arab robes. A motorbike bearing an Abu Dhabi number-plate stands outside a gift to the hotel’s owner, who also possesses a jeep.

He is an effusive man who is more than happy to talk. He knows that some children and their guardians have been arrested at Karachi airport. He confirms that children are being sent to the UAE as camel riders but denies the report that they are beaten. He maintains that the child riders (who also include boys from Sudan and Oman) are tied to the camel’s back, with a strap resembling a seat belt.

“These races in the Arabian deserts are centuries old,” he says. “Pakistani diplomats in the UAE, Pakistani ex-patriates and army officers serving there are among those who flock to see them.” He has been to one race himself. He admits that sometimes riders fall off the camel’s back, but he does not know their fate. “What is more important,” he says, “is that the Sheikhs pay fairly handsome compensation if there is an accident-between two to three lakh rupees.”

The eldest of the boys remained silent throughout this conversation, staring out of a window. Another boy, who seemed to be the youngest, kept | constantly crying. He appeared to be sick, but asked if the child was unwell, his father casually replied, “He’s all right, just restless.”

He attributes the use of children to the “Arabs’ obsession with speed. They buy special lightweight camels for these races, and control their diet to keep down their weight. The ideal weight for a rider is about 15 kilograms, which is why such young children are imported. Those who cross the weight limit become useless, so the age limit tends to be seven or eight.”

Usually from 30 to 40 camels take part in a race. The first prize is 10,000 dirhams. A great deal of betting also goes on at the races.

The hotel owner says that children have been going to the Emirates for the past seven years. In the beginning it was a secret but now “all the greedy people are sending their children.”

Chak No. 17, in Khanpur tehsil, is one of the poorer villages in the desert.

Drinking water has to be brought from two miles away. The people here live in huts built of straw. This is camel territory par excellence. Camels are a normal feature of life here and even young children can often seem on camelback. A young boy walked past and was eager to talk. He said many of his friends had gone to Abu Dhabi. Some of them visit the village once a year and appear to be very happy with their jobs in the Emirates.

The majority of the children who have gone to the Emirates belong to the desert. Most families here own ani- mals and live mainly on the income from hides and milk.

But though large numbers of people from Cholistan are sending their children to earn money racing camels in the Emirates, there are also people here who don’t approve of the practice. The father of a child riding a camel says he would never contemplate sending his son to the Emirates to become a camel jockey. “We are poor, but we have dignity.”

Ascot in the Desert

It might not be Ascot but it brings out the crowds – and that includes royalty. It is also perhaps one of the last vestiges of the Gulf’s old Bedouin culture.

But these desert races are different from their western equestrian counterparts in one respect: the riders are young boys – some no more than six. Most of them are Arabs from Sudan and Oman (never local Arabs), but now boys from India and Pakistan are also being imported.

Sponsored by the rulers of the seven emirates, including UAE President Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan, camel races are held mainly in the winter months in Al-Ain, Sharjah and Ras al Khaimah. The bigger races are major events and are televised live throughout the Emirates.

The show begins at the crack of dawn. At first you get the impression that it’s a four-wheel-drive rally, and that the camels are merely part of the landscape. It soon becomes clear, however, that the Pajeros, Land Cruisers and Range Rovers belong to the spectators – camel owners, local notables and members of the public.

The build-up to the race is quite exciting. Older locals, with memories of a simpler past, sing traditional songs, accompanied by a welter of percussion instruments: bells, small castanet-like cymbals and the Arab ‘duff’. A group of men perform the sword dance in one corner and a qahwa ceremony takes place in another. White-robed Bedouins squat among the dunes. A scene straight out of the Arabian nights.

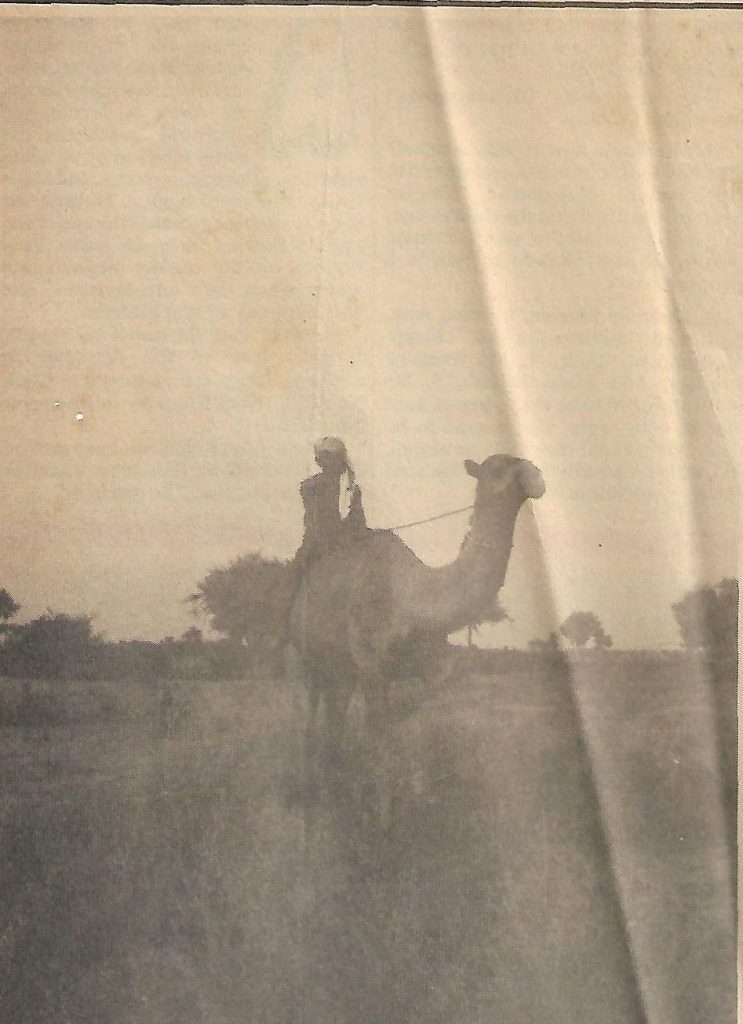

Excitement builds up among the crowd as the riders prepare to mount. Because of their age and size, some of the boys – who are as young as six – are strapped onto the camel with their backs resting against its hump for support.

This is a dangerous — and precarious method, not much because of the camel’s speed (never very fast) but because the animal tends to slope backwards when it runs. A fall from a camel’s back can be nasty: it stands about nine feet off the ground from hoof to hump. However, serious accidents are rare.

According to experienced camel-jockeys, the camel is a calm and placid creature. It has a reputation for being stupid and obstinate and tends to grumble noisily when forced to undertake any strenuous activity. It will often refuse to run if overloaded, hence the very small, lightweight riders.

At the end of the race the winner is awarded a handsome cash prize and often a young camel. But this being the Gulf, every participant gets a substantial sum of money as a consolation prize. The latest trend in gifts at royally-sponsored races include four-wheel-drive vehicles.

The race begins on a fenced-off track often ten kilometers long. At least one four-wheel-drive vehicle follows the camels throughout the race, carrying paramedical equipment and enthusiastic camel-owners. Even at its fastest, the camel’s pace is sedate, rather like a giraffe’s: its normal speed is not more than about 10 k.m. per hour (6 m.p.h.). One extreme method used to make camels run faster is guaranteed to raise the hackles of animal liberationists: a sore is cultivated on the camel’s neck and pricked constantly!

At the end of the race the winner is awarded a handsome cash prize and often a young camel. But this being the Gulf, every participant gets a substantial sum of money as a consolation prize. The latest trend in gifts at royally-sponsored races include four-wheel-drive vehicles.

There is one other interesting aspect to the occasion: a relaxed atmosphere prevails and most formalities are dispensed with. Unusually, the locals, irrespective of their status and awesome titles, are approachable here and willing to laugh and mingle with total strangers. There is little sign of the paranoia that normally characterizes their attitude to aliens today. One gets the feeling of having been transported to the Gulf’s past.